Rupi Kaur’s Home Body revisits themes readers will find in Kaur’s other poetry books (she returns to her familiar haunts of depression, anxiety, sexual assault, rape, love, masturbation, and hope), and while the book (like her others) could benefit from some judicious editing, I also can’t help but feel the embrace of a writer who holds her teen and young women readers close, perhaps too close, with words that may not be perfectly polished, but may be exactly what they need to hear.

Kaur wrestles with the consequences of her own success in Home Body. At 28 years of age, Kaur has done the impossible. She has sold over 8 million copies of her books of poetry. Can she top herself? Can she grow and maintain her audience? If her audience grows with her, I think she can do both, just not quite in this book.

I had hoped after reading Milk and Honey (which I review here) that Kaur would mature as a writer. In some ways, Home Body does offer us a more mature Kaur. The second poem in the book unfolds with uncharacteristic restraint. By withholding the subject of the poem, Kaur evokes a sense of suspense. It’s a simple tool in the poet’s toolbelt, but it’s promising to see Kaur taking her first steps into exploring the richness of the poet’s rhetorical options.

Kaur isn’t a mature poet, but she’s finally joined the upper divisional poetry workshop. When she writes “i have never known anything more / quietly loud than anxiety,” I couldn’t help but applaud her deployment of the well-timed oxymoron.

There is a hasty feeling to this book, the sense of someone fretfully and fitfully sitting in a room for a few nights, hashing it out. Later in the book, Kaur exhibits some self-awareness on this front, writing “your rushing is/ suffocating the masterpieces.” Many of the poems do feel rushed. The old themes could have been let go, or given more time to mature. The new themes perhaps needed more time to develop. There’s a “work in progress” feel to this book, but perhaps that is its charm.

And perhaps, as a “young adult” book of poetry, there is an appeal to something written more for commiseration than introspection. As a teenager I read Arthur Rimbaud and Mary Karr, and I relished in their depths, in their ability to be indirect at times, in their ability to push the language to its limits. Pushing the language to its limits is not Kaur’s project.

Kaur’s Home Body is more self-help than poetry, and perhaps that’s okay. There’s a list poem “of things to heal your mood.” We are, after all, living in the midst of a global pandemic that has killed 250,000 people. We are all feeling a little isolated and a little beside ourselves, and maybe not always in the mood for Keats, or John Donne. And while I might not be in the mood for Donne’s “Criterion Collection” of “Batter my heart, three personed God,” I do have the space for the “Netflix and Chill” of Kaur’s “i want something to/hold me by the neck/split me down the middle/and make me feel alive again.” We’re all feeling a little (okay, a lot) isolated, and beside ourselves. A “list of things to heal your mood” is not a bad addition to the verbal landscape.

While Kaur’s words lend themselves best to the Instagram format, where they perhaps live their best life, there’s something nice about looking at a physical blank page with only one line on it that says, “our pain is the doorway to our joy.” The bravery of the blankness and the risk of aphorism deserves its applause. Printing shit on paper costs money. It takes courage, girl.

Where the book does more with less, it is best. The short poem, “i’m surprised I got out at all” envisions in three lines a relationship so small and entrapping, the hostage can’t “see the exit.” The claustrophobia of the relationship is echoed in the claustrophobic brevity of the poem. Brava. Like I’ve said about Kaur’s other work, I wish she’d edited herself; I wish she’d separate the wheat from the chaff. Here she does it.

There is something almost Sapphic to the three-line poem “why does everything / become less beautiful / once it belongs to us.” And there’s something beautiful about the fact of the plainly spoken when it has perhaps not been plainly spoken in poetry: “What if the one I want / is someone who touches me and leaves.” Here is a young woman coming to terms with the complexities of romantic love, the paradoxes of being young and a woman in this society that shames women for their sexuality. There is the need we all have for comfort, and the desire we all have for the thrill of the chase, for the untouchable, for the risky, for the dangerous. We should all be 20 and wild and in love and in doubt and chasing what we cannot have, and Kaur captures some of this feeling. She evokes the unspeakable: that there is a kind of thrill in abuse and a kind of boredom in secure love.

But her concept of love is not boy-crazy, which is why I keep coming back to the idea of this book as self-help for teens and young women. Kaur offers her readers possible ways to be a woman in our society, and dammit, our world needs more possibilities that aren’t purely cerebral or theoretical or found in a primer for an undergraduate Women’s Studies course.

She punctuates her section on love with: “masturbation/ is meditation,” reminding her readers “i’m careful about/ who i spend my energy on.” The section of Home Body called “Heart” really should be called “Body.”

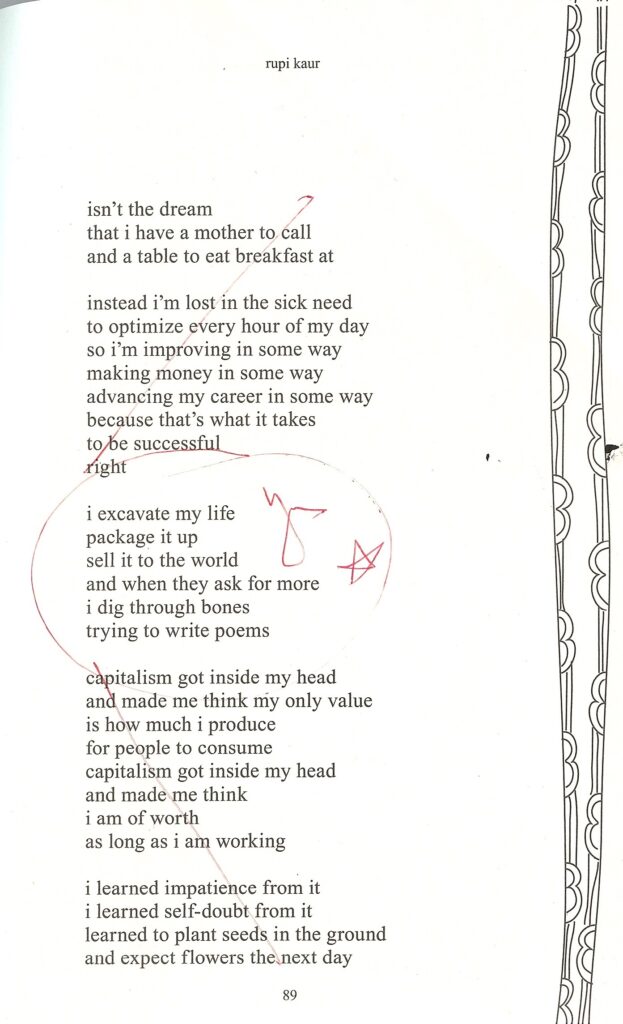

Her poem, “Productivity Anxiety” could have been shorter. In fact, I’d cross the whole thing out except for one stanza.

Kaur’s critique of capitalism in this same poem is good, but it belongs in another poem altogether, perhaps in the beautiful poem she writes about her dad’s life as a truck driver. Kaur is wrestling with important ideas here. I hope she gives them time to breathe and grow in her next book. I hope she finds the language to transform them into a deeper art, because we need voices with the reach to convey these ideas clearly to the next generation.

Kaur also takes early inroads into eco-poetry; and it is some of her best work, like the poem on page 101.

Kaur is wrestling with her success in this book, and in the process finds new subject matter. Kaur’s interrogations of capitalism, her deeper explorations of her working-class background, her forays into black lives matter poetry, and her commentary on our culture of self-help and productivity are seeds for future books. She writes: “Even if we managed to/ make all the money in the world/ we’d be left feeling empty for something/ our souls ache for community.”

I still found myself getting my red creative writing M.F.A. pen and doing edits. There are some brilliant poems hiding within some longer movements.

There are too many ideas here competing for airtime. Kaur has lifted her poetic antennae, received the signals of the culture, and taken her notes. I wonder what would happen if she approached her next book in a more organized manner, with a clearer mission; I wonder what would happen if she pushed her work, really challenged it. Kaur writes: “the future/ world of our dreams/ can’t be built on the / corruptions of the past.” If Kaur is to move forward and grow as a poet, I think she needs to let herself change, to risk a transition.

Poetry is all about the art of mastering transitions: verbal transitions, thematic transitions, and the life transitions that often become poetry’s finest subject matter.

In my legal content writing, I often find myself writing for people facing major life transitions, whether it’s the person who has been seriously injured in an accident, the person going through a divorce, the person whose life has been changed by crime, or the person making end-of-life plans. There is a kind of poetry to be found in our moments of greatest uncertainty. Poets have mastered this art. But if Kaur shows us anything it is that there is poetry to be found wherever we write about these transitions. Poetry can be anywhere; everywhere. Kaur reminds me to find the poetry everywhere.

About the Writer

Janice Greenwood is a writer, surfer, and poet. She holds an M.F.A. in poetry and creative writing from Columbia University.